Joe Sacco’s contributions to both comics and journalism have been an inspiration for two decades. His skill as a reporter combined with his unflinching talent as an illustrator has solidified him as one of the finest independent creators working in the medium today. Join Broken Frontier’s Steven Surman as he examines Sacco’s three major works and their enduring validity.

The latest volume of Joe Sacco’s illustrated journalism, Footnotes in Gaza, is quite possibly his finest yet. There’s an evolution at play in Sacco’s three main nonfiction works: Palestine, Safe Area Goražde, and now Footnotes in Gaza. His first and most well-known is Palestine, and in the pages of the book itself, Sacco says it’s his “magnum opus” (an author’s “great work”). But when compared alongside his later contributions to both journalism and comics, it’s not his outstanding creation.

Palestine

Palestine tells the powerful story of Sacco’s immersive journey in Palestine during 1991 and 1992, detailing the atrocious everyday living conditions of the Palestinians under the occupation of Israel, a torturous situation that’s been seething since the early years of the twentieth century. Palestine illustrates (literally and figuratively) a truth the western world, particularly the United States, has a hard time grasping: Israel isn’t a state of sugar and spice and everything nice that has no blame for the violence that ceaselessly plagues the Middle East.

It’s his motivation to tell the other side of the story concerning the Israeli/Palestinian conflict that shines throughout in Sacco’s Palestine. He takes great care to document not only his experiences traversing the eye-opening slums of Palestine, but also to record the horror stories that many Palestinian civilians have to share about their condemned lives. Of that, Sacco does his readers an immeasurable service.

But his book is also a bit cavalier at times, which peeks through in both his narrative and art. Sacco seems certain here and there that he’s going to be the one who breaks through the conflict and discovers a final course of resolution. As I read Palestine for the first time last year in 2009, I couldn’t help but feel that Sacco wanted to craft his magnum opus instead of just letting the story flow as it would. This isn’t a criticism as much as it is an observation, because the work is wholly breathtaking when considering the quality of the entire piece as well as the courage of the message.

And Palestine is a work that’s no stranger to criticism: I’ve heard several accusations made against Sacco, claiming that he’s a propaganda machine working against Israel. But Sacco himself addresses this in the book; there’s a scene depicting an argument he has with an Israeli woman who makes this charge: “Shouldn’t you be telling our side of the story, too?” Sacco’s response: “I’ve heard nothing but the Israeli side [almost]all my life.” Too true.

Safe Area Goražde

Sacco’s second major piece of illustrated journalism, Safe Area Goražde, was the first book I read by him; I was attracted by the forward of Christopher Hitchens, a journalist and author I greatly admire. But even if it weren’t for Hitchens, I would have found my way to Safe Area Goražde eventually, because there’s no other work out there quite like Sacco’s. There is a handful of well-crafted nonfiction comics currently in publication, but most are memoir in nature, and I’ve never come across any with the journalistic spirit that Sacco’s has.

Here, the cartoonist shows us his journey from 1994 to 1995 through the town of Goražde (pronounced go-RAJH-duh), a “safe area” in Bosnia that remained untouched by the ethnic cleansing of Muslims by the Serbs during the Bosnian War. As with the fashion of Sacco’s other books, this is a work of immersion journalism, a reporting technique where the journalist immerses himself into a situation and narrates directly from his own perspective, acting as a tour guide of sorts.

But also common in Sacco’s books are asides that reflect the tragedy and hardships of the various subjects he interviews. One reoccurring character in this story is Edin, a college student who was studying in Sarajevo before the war, but he eventually returned home to help protect his family. Edin is one of the strongest character portrayals I’ve ever seen in Sacco’s work—he’s richly developed in both personality and appearance. Sacco tends to sensationalize the appearances of the people who are documented in his books, but Edin’s handsome features remain stoically intact as he narrates his various tales of tragedy and survival during the Bosnian War.

Sacco’s tone in Safe Area Goražde is much cooler and more sober than Palestine. There are no lofty attitudes, and the angst he feels here is much more empathetic towards the people and circumstances around him, rather than giving the blunt impression that the final book is all that ultimately matters. And that same empathy reaches out to the readers, as well. The stories revealed in Goražde are heart-wrenching, and more than once I felt that Edin was much more than a cartooned image translated from copious notes, but rather an actual person telling me about his war-torn life. Journalism of that caliber is a rare talent.

Footnotes in Gaza

The evolution of Sacco’s work has reached its zenith in Footnotes in Gaza. Sacco’s capacity as a storyteller has never been stronger, and his artwork is purely breathtaking. As an artist, Sacco has always placed great care in capturing every fine detail in the environments and locations he visits, and not a single facet is missing in Footnotes. He inquisitively tours every area and takes photographs. If something is no longer standing, he reconstructs these places from secondary research. But unlike his other books, Footnotes doesn’t sensationalize the appearances of the interviewees. Sacco’s pencil has never been so objectively fine in illustrating his subjects.

As a storyteller, Sacco’s finesse is doubly needed, as this is probably the most difficult tale he’s had to tell. Unlike Palestine and Safe Area Goražde, which are largely real-time, this book is reconstructing two bloody events that were largely ignored and then forgotten by the selective memory of the West pertaining to Middle Eastern affairs. The two stories the cartoonist is after: two massacres that happened in November of 1956, one in the city of Khan Younis and the other in the town of Rafah.

The fated day in Khan Younis was preempted by the Egyptian occupation of the city; it was their only outpost in the Gaza Strip that resisted the Israeli invasion. To ensure that no further opposition would take place, the Israelis killed anyone who they thought posed a threat. But the truth of the matter is they used the opportunity to slaughter as many Palestinians as possible under the guise of squelching a resistance. Homes were invaded and fired upon; Arab men, young and old, were lined up against walls and gunned down on November 3, 1956. So many bodies were there that the wives and mothers of the slain unhinged the doors of their homes and used them as gurneys to carry their dead.

The lesser known but more atrocious event occurred in the town of Rafah on November 12, 1956; it’s infamously referred to by the people of Gaza as the “Day of the School.” The morning of the twelfth, Israel soldiers rode through the streets of Rafah making the ominous announcement that anyone between the ages of 15 and 60 (respectively; Sacco received varying recollections, but all were consistent with men of military age) to report to the town’s school.

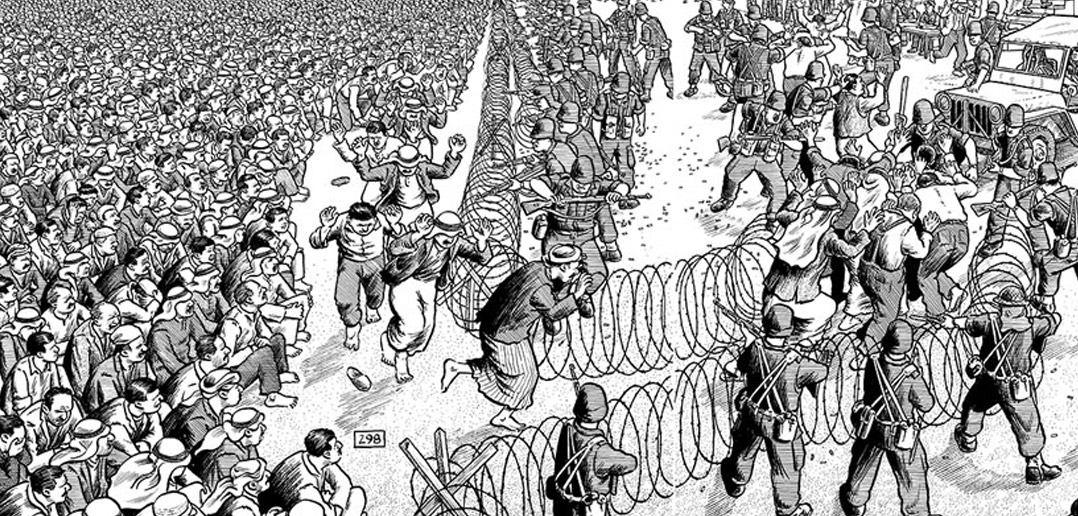

Once the announcement was made, the day turned into a death march for the Palestinian men summoned. As they walked to the school grounds, they were continually fired upon by Israeli soldiers, and the first wave of victims fell to the ground either dead or bleeding. The survivors that reached their destination were lined up against a wall that enclosed the school’s courtyard and fired upon. Those who were not dead were ushered through a perverse obstacle course of sand pits and barbed wire while Israeli guard clobbered their newfound prisoners with clubs. These survivors were held captive in the courtyard and forced to stew in their own defecation while Israeli soldiers screened potential resistance fighters. When the screenings were complete at day’s end, the prisoners were released in such a fury that they tore the wall down to escape.

Juxtaposed again Sacco’s exploration of Gaza’s bloody past is the truth of squalor that haunts the streets of the Gaza Strip presently. The elders the cartoonist interviews have their own unique stories to tell, and while some desire a cathartic opportunity to purge the past, others don’t want to remember. The younger generations of Palestinians, however, reject Sacco’s desire to learn about past horrors when the present is ripe with suffering. There’s a particular occasion when Sacco visits a bakery with his research assistant. When the shopkeeper learns of Sacco’s book, he has a curt response: “Forget about the past. What about now?”

The Cartooning War Correspondent

Sacco’s contributions to both journalism and comic books exceed these three titles, and my decision to single out these books in particular is arbitrary. But what these three books offer are the contained pursuits of one man doing what he can to shed an honest light on the vague immoralities that pollute the world around us.

Sacco is a war correspondent, but he’s not embedded. He goes it alone, wandering ominous streets and interviewing dangerous people for the sake of finding the story. He has assistance, yes, but his Virgils are always research subjects themselves, and their knowledge of the hells he’s exploring are unparalleled. Sacco makes friends, discovers who to avoid, figures out where to go, and develops a rare knack for keeping himself honest.

I mentioned earlier that Sacco engages in “immersion journalism”; this is important in understanding exactly why his work speaks honestly. As a journalist, he doesn’t pretend that his presence in these ravaged areas has no effect. Instead of ignoring this aspect of his reporting, he embraces it. He speaks in the first person, addresses his readers, and tells us what he is feeling and thinking about everything that is happening around him.

Of this balance, Footnotes in Gaza hits its stride. It’s Sacco’s most sober and dedicated work. Again, that is an arbitrary observation, as the depth and breadth of Palestine and Safe Area Goražde are unlike anything I’ve ever seen in both comics and journalism. There’s an uncanny fusion of illustrations and words that Sacco captures in the work he produces: he’s able to not only speak to us through sleek and sincere prose, but he’s capable of showing us aspects of the world that we’ve never seen—and would never want to inhabit.

Sacco has found peace with his role as a storyteller, solidifying him as one of the best out there—both with words and imagery. But that begs the question: why illustrations? Wouldn’t the reporter’s brand of war journalism be better served employing a medium like fumetti? I’m not so sure: savvy photojournalism is capable of conveying the harshest yet most moving aspects of the human experience with a single image.

It would be an easy pass to claim that Sacco couldn’t make his books with only photography because many of his stories are recollections distilled from interviews, and camerawork simply isn’t an option. But there’s a deeper significance: if photographs reveal the material of life, then illustrations expose the spirit of life. They convey a level of emotional symbolism that the mechanisms of a camera can’t; the artist’s tools are indispensable when reality fails us.

The histories of Khan Younis and Rafah could have easily faded into history—to be fair, they mostly have—but Sacco took the time to conjure up the ghosts of the past so we may witness them now in the present and remember them in the future. This is the gift of Joe Sacco’s work. But it’s a gift than can easily be lost, and it’s our task to exercise remembrance.

This essay originally appeared on Broken Frontier.