Here is a quote to consider: “[Karl Marx’s] real mission in life was to contribute in one way or another to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the forms of government which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation of the present-day proletariat, which he was the first to make conscious of its own position and its needs, of the conditions under which it could win its freedom.” This statement was made by Friedrich Engels in 1883 at Marx’s funeral, and its pithy insight cleanly summarizes the mission of the world’s most famous communist.

The above quote also captures the very element of communism that Dr. David Conway, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at Middlesex College in the United Kingdom, wishes to refute in his book, A Farewell to Marx: an Outline and Appraisal of His Theories. Marx’s communist beliefs have been both lauded and loathed by many around the world for almost two centuries, and it is Conway’s premise that communist philosophy needs to be critically evaluated and dismissed in the present day for its fanciful and unruly propositions.

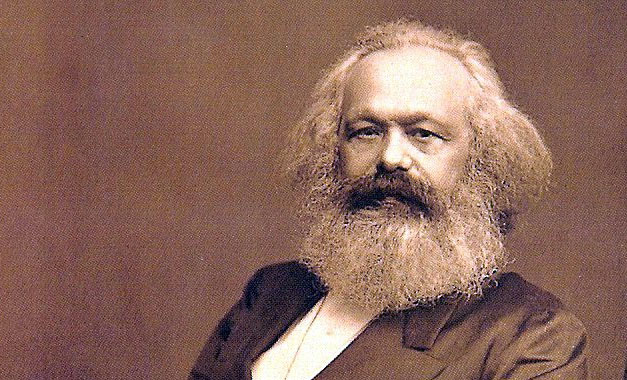

Karl Marx was born in Trier, Germany in 1818. He became an official communist in 1843 while working for the Rheinische Zeitung, a newspaper where he wrote critical articles about the treatment of the poor by Germany’s monarchy of the day. It was this journalistic activism that sparked a fire in Marx, a spark that would lead him to the communist beliefs of his philosophical forefathers, such as Gracchus Babeuf, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen.

To anyone just vaguely familiar with Karl Marx and his writings, there are some easy-to-recognize basics about his vision of communism. Marx believed in a war between capitalism and communism: capitalism’s ultimate profit-driven ideology will always undermine the greater good of the masses, whereas a purely communist society would place all power into the hands of the people for the guarantee of a fair and just world.

In both Marx’s writings and Conway’s analysis for refutation, it’s important to note the communist position that capitalism causes a mean-spiritedness that is not natural to the human condition. This is because when dollars and cents are entered into the equation, everything else becomes secondary, including the well-being of the workers who produce the goods and services required for capitalism’s survival.

If capitalism is the problem, then, as Marx predicted, it will eventually fall. And from its ashes a communist utopia will arise where labor is no longer a necessity but a luxury. Minimalist work will be abolished and everyone’s creativity will be allowed to flourish. This liberation will be fueled by a collective wellbeing, and there will no longer be the need to earn a paycheck at the end of the day. But Conway is understandably skeptical of this vision, writing the following: “First consider the claim advanced by Marx that communism permits each individual to do what he likes, as he likes, when he likes during the period of work. This, surely, must be rejected as purist fantasy.”

But Conway’s solutions are of the same theoretical lot as Marx’s; they’re just an opposite paradigm. Where Marx promoted total and complete communism, Conway simply promotes total and complete capitalism from the beginning to the end of his analysis. Recognize that A Farewell to Marx was originally published in 1987, at a time when both the Reagan presidency and the Thatcher ministry were winding down in the West, and the two leaders prompted heated debates about the power of capitalism over that of the state.

The time frame of the book’s publication also dates the material discussed in its pages. It’s been over 20 years since Conway first wrote the book and the balm of unfettered capitalism that he proposes as the true source of happiness doesn’t always hold up. In the book, he says: “If capitalism divides up the way work is distributed amongst members of society in a way that makes work unfulfilling for many, it does so because such a division of labor has been found to be more productive than a distribution that offers more fulfilling work.”

Conway’s point is that Marx demands the freedom of creativity in work, so no one is stifled. Conway doesn’t believe this is possible if a legitimate economy is to be built. But the author’s own point misses what Marx is saying: It’s not just the profit of capitalists that should matter, but also the happiness of the workers. This is the divide of Conway’s sometimes ivory-tower approach of capitalism versus communism and their applications in the working world.

A Farewell to Marx raises legitimate questions and concerns about the underlying meanings and intentions of Marx’s philosophy. How exactly can communism truly be taken seriously after evaluating it against the functions of the real world? But inadvertently, Conway draws his own conclusions into question, too. The current global economy is in peril; wage stagnation is at an all-time high; service-industry jobs are the fastest growing and lowest paying occupations available. Conway says that communism isn’t the answer. But, considering how things are going, neither is a purest approach towards capitalism. A Farewell to Marx has raised a much more elemental inquiry: what exactly is the answer?

This book review was originally published by Simply Charly.